search

date/time

| North East Post A Voice of the Free Press |

Artis-Ann

Features Writer

6:13 AM 8th September 2021

arts

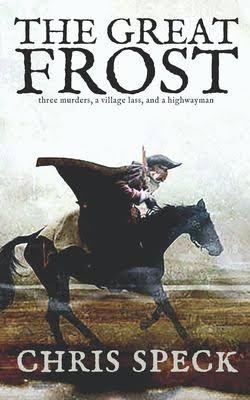

‘You Have To Take Your Chances When You Can’: The Great Frost By Chris Speck

This latest novel by Chris Speck is a great yarn, with real villains and romanticised outlaws, plenty of action and a nucleus of believable characters with whom the reader becomes well acquainted. There’s Meg who lives with Nana and the boy, Richie. Her husband went off to fight in the campaign led by the Duke of Marlborough against Louis XIV of France four years before, and never returned. No one expects to see him again. Meg tends to the chickens and the pigs for Mr Pennyman, the local landowner, and try as she might to do the right thing, it appears that girls of her class, in her situation, will rarely be thanked, even when she risks her own life to save others.

Nana, ‘nasty as a raw wind…bitter as rhubarb’, has learned to use her ailments to her advantage and doesn’t make Meg’s life easy but ultimately, cares for her neighbours and lives her life through her daughter in law, Meg.

Chris Speck

The reader quickly allies with these characters and feels for their plight. There is sympathy for Meg who says ‘I don’t believe in love…it doesn’t fill your belly or keep the house warm. Duty, I understand’, as she toils daily to keep the little family together, knowing her place and doing what is right: ‘Bad jobs have to be done and it seems it’s Meg who has to do them.’

Life is complicated by the arrival, one night, of a badly wounded highwayman. Meg has learned from her mother ‘how to heal’, and they hide ‘The Robber’ and help him, despite the real danger he brings to their door. He also brings a hint of romance, at least in Meg’s dreams, to soften the reality of their hard existence. His former associates, Dandy Jim and Carlos, search for him and briefly turn Meg’s head, while her mother’s dying words give her strength: ‘there is a time to speak, a time to listen…time to speak and time to act’.

The real villains are not obvious, issuing thoughtless violence: a slap, a blow and much, much more, and the locals, knowing their place, are afraid. ‘Nobody has a thought for the first dead body…nor the second… they do not wish to be reminded of it’, while the local constable, Danny Reed, is ‘torn between duty and humanity’.

Also by Artis-Ann ...

Spying Is Lying: The Traitor By Ava GlassFlawed Characters:The Party House By Lin AndersonAn Extraordinary Life: Three Things About Elsie By Joanna CannonWhat A Tangled Web: Wartime For The Chocolate Girls By Annie MurrayPoems And Pressed Flowers: The Botanist By M. W. CravenI was drawn into this tale early on and became quickly absorbed; the historical detail of life in the early part of the eighteenth century lend it authenticity, allowing the reader to share the grim and precarious existence of the characters. Definitely recommended.

The Great Frost is published by Flat City Press